|

| With thanks to the LSE Women's Library |

It is not clear whether the sentiment of the poem - "To the Old Year and the New" - was occasioned by the turn of 1909 into 1910 (looking forward hopefully), or of 1910 into 1911 (relieved to leave that one behind). Anyway, it's a nice photo of Herbert - which we will see used again in the General Election. As for 1910, was it annus mirabilis or annus horribilis? Find out below.

Crossing the Rubicon

Last time - here - we noted that in April 1910 the non-militant women's organisation, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, decided to run candidates at the next General Election in constituencies where the sitting member holds his seat by only "a small majority, and is an Anti-Suffragist". This was provoked by the Government's intervention to block the Conciliation Bill after initial progress in the Commons. Professor Angela John - who has been far more perceptive in her reading of the MLWS Monthly than I could ever be - notes that the October 1910 issue reports that the League "crossed the Rubicon" at a special meeting in September, when it, too, voted to "adopt a policy of distinct opposition to the Government" (John (2000)). The League's new position prompted resignations from its ranks by some Liberal MPs. It also set the scene for Herbert's candidacy in East St. Pancras.

The 2nd General Election of 1910 took place over the period 3rd to 19th December (oddly, different constituencies voted on different days). It was called by the new Liberal Government to overcome the (inherited/appointed) House of Lords' veto on (elected) Commons' legislation, and was thus a constitutional clash between the elected and non-elected. It was The People versus The Peers, as The London Daily News dubbed it. By contrast, in East St. Pancras women's suffrage seemed to be the focus, even if "hardly the way to meet a great issue like the Veto question" (The London Daily News 26 Nov 1910). The overall General Election result saw the Liberals squeeze home with one extra seat, and the Lords backed down. This Great Historic Showdown led to the Parliament Act of 1911 which supposedly resolved the problem once and for all.

Standing for Women

As we noted last time, the first site of the new pro-women's suffrage parliamentary intervention was South Salford where the local NUWSS Branch persuaded H. N. Brailsford (a Men's League stalwart) to stand against a Liberal Anti-Suffragist Hilaire Belloc, upon which the Liberals withdrew their man, substituted an acceptable candidate, and everyone was happy (though maybe not Belloc). Regret: no such convenient solution in St. Pancras East - Herbert's battle-ground.

It was the London NUWSS Executive Committee who first adopted Jacobs' candidacy (on November 16th) after analysing the conditions in several London constituencies. The London Society's Secretary, Philippa Strachey (sister to enthusiastic chess player Marjorie, who we blogged here, and to brother Lytton - see here) was his Election Agent. The decision was approved by the National body two days later (Report of the London Society of Women's Suffrage 23 January 1911). Another seat was fought in Glasgow.

Jacobs v Martin

The Liberal incumbent was Joseph Martin, now defending a majority of nearly 700 against Tory John Hopkins (later a Sir, and a Baronet). That was a 9% (more or less) majority in a poll of nearly 7000; whether that was "a small majority" or not by the psephological standards of 1910, I couldn't say - though others did, and thought Jacobs intervention might split the Liberal vote.

Here is the Herbert's address to the electors of the constituency:

|

| With thanks to the LSE Women's Library |

Its very first line is "I am offering myself as a Liberal Candidate", and it finishes by saying "on other questions I feel that I should be able to support the Liberal party". As there was already an incumbent Liberal this became a resigning issue for some, and a few members of the Society for Women's Suffrage returned their cards (per letters in the LSE Women's Library file). As for women's suffrage itself: Jacobs was of course in favour - perhaps this was his USP compared with the other Liberal.

The London Women's Suffrage Committee advanced an additional reason for standing in St.Pancras East: Joseph Martin was "unpopular among sections of his party, and had given offence to many of the Liberal women." One imagines Mr Martin couldn't have cared less. He was a veteran of the rough and tumble of Canadian politics where he had also rubbed people up the wrong way: friend and foe without distinction. This is what the Dictionary of Canadian Biography says about him (and they should know).

"His quarrelsome nature and his tendency to resort to his fists to settle disputes would soon earn him the nickname Fighting Joe. Suspicious in nature and with a capacity for pettiness, he would be known throughout his career for his feisty, combative spirit. He would also demonstrate considerable eagerness to advance his own interests."Did Herbert know what he was letting himself in for? He was to find out when he politely raised with Martin the issue of disruptive heckling at Jacobs' public meetings and the "excess of zeal which a few of your supporters display by violating the essential principle of free speech." (copy of letter 28 November in LSE Women's Library). "A joint appeal from the two Liberal candidates" might restore "fair play" suggested Jacobs innocently. This is page 2 of Fighting Joe's answer - after venting his spleen on page 1 on related matters:

|

| " I do not understand why you should come squealing to me." With thanks to the LSE Women's Library |

As for Martin's own offer to the gentleman electors of East St. Pancras, here it is below, and you will notice the claim at the end that "I support.....Votes for Women on the same terms as men." This, of course, was the nub.

|

| With thanks to the LSE Women's Library |

He had also gone further than simply accusing Jacobs of splitting the vote: he alleged (in page 1 of that letter) that Jacobs could have been "put forward by the Tories" - though he disingenuously said this charge was voiced by his "supporters".

He was in even higher dudgeon over the suffrage issue. "I have always supported votes for women.." he claimed - sounding indistinguishable from Jacobs. However, he went on: "I am opposed to the Conciliation Bill because it is a Tory measure and proposes to give votes to rich women [who would supposedly vote Tory - MS] and not to poor women [who would vote Liberal]. His (self-interested) point was that the Conciliation Bill compromise - to extend female voting only to single women householders, and married women where the house was in her name - would lock a political bias into the franchise. Martin was not only "opposed to" the Bill, but - moreover - he had voted against it: this was the principal, and principled, reason why the London Women's Committee targeted him.

Letters to the Editor

Mrs Fawcett, head of the NUWSS, gloved-up and wrote to the Times (reported 3rd December). She took Martin to task over his election propaganda and position on the Conciliation Bill: "he would oppose all gradual and moderate extension of the Parliamentary franchise to women and could vote for no measure of women's suffrage short of complete adult suffrage." She added that when she challenged Martin she could get nothing satisfactory from him: this was at a meeting between the NUWSS parliamentary officer and his good self on 30th November - held, incidentally, without Jacobs' knowledge (Report of the London Society of Women's Suffrage 23 January 1911).

Fighting Joe wouldn't let that go unanswered and counter-punched with his own letter dated 3rd and published in the Times 5th December, repeating publicly the allegations he had made in his letter to Jacobs just a week earlier: Jacobs was a "recipient of Tory Gold" (as Jacobs interpreted the charge elsewhere), and the Conciliation Bill favoured rich Tory ladies. Martin's letter was conveniently published just before polling. The Times editors may have solicited a response from the other side, for into the ring now stepped Conciliation Bill champion H. N. Brailsford (him again), chair of the Conciliation Committee and Men's League heavy-hitter.

His letter was published on polling day. The Conciliation Committee had done their home work - or rather, their field work. Brailsford refuted the claim of a Tory bias in the compromise franchise proposal by quoting the result of "house to house investigations" which revealed that 89% of women on the municipal roll "are working women". He also pointed out that the Committee itself was composed of "37 Liberal, Labour and Irish members of Parliament, with a minority of 17 Unionists". Thus Martin was, he implied, a no-compromise extremist out of step (not, of course, for the first time) with pragmatic Liberal colleagues.

It remained to be seen how this difference over the efficacy of the Conciliation Bill would play out with the electors of East St. Pancras.

On the Stump

Jacobs' constituency campaign had cracked on, with "numerous open-air meetings and a mass canvass" (MLWS Monthly Dec 1910). Women responded to the appeal of the London Women's Committee for canvassers, carriages, cars (motor) and cash: £700 was needed for the candidate's expenses. 12 Members of the Executive of the NUWSS came over to help, as did members of 13 local branches (London Committee Report op cit). The LSE Women's Library Archive has a number of letters showing support and giving money, including this one:

|

| £5 from Mrs Larkcom-Jacobs |

Of course, men from the MLWS also went to help, including to speak at campaign meetings (Brailsford for example), even though Jacobs was not an official League candidate (that would have violated the League's political neutrality). As discussed above "hecklers were extremely attentive", with the same "artists in interruption" appearing repeatedly - but acknowledging "the good temper with which Mr Jacobs and his speakers had endured...'a regular gruelling'" (MLWS Monthly).

Result! Result?

The result was declared, and reported in the London Daily News in a Special Election Edition the same day: Tuesday 6th December.

Martin held the seat. At least no one could now accuse Jacobs of splitting the vote. The other Suffrage candidate Mr W. J. Mirlees in Camlachie Division, Glasgow, did better: he polled 35.

The press had a field day, with the Portsmouth Evening News later (Jan 4 1911) relishing that Jacobs' votes cost £17 1s 6d each in election expenses, and Mirlees's £9 11s 4d. And there was the 'back in your box' glee of the Globe: "Mr Jacobs is, we believe, a most amiable gentleman....and, we understand a quite a good chess player....[but] no Radical or Unionist...has had to suffer the peculiar indignity of motor-cars waiting outside his committee rooms to bring up voters who did not exist...If they would show some intelligent interest in general politics, instead of shouting 'Votes for Women' in the din of an election they would go far to make the men think they ought to have the vote" (6 Dec 1910).

Jacobs put the best gloss in it that he could, for example in letter in the LSE Women's Library to a supporter (December 13th) he says "The poll was unfortunately very small, several local people of influence have informed us that the fortnight's campaign had a wonderfully good effect in rousing people in the neighbourhood the importance of the question." The MLWS Monthly in January 1911 also referred to the "want of preparation" in the constituency, and that the other candidates had voiced support for women's suffrage (whether disingenuously or not) - thus drowning out Jacobs' more nuanced advocacy of the Conciliation Bill as the concrete route to "Votes for (Some) Women".

There had been, as we noted above, polite rumblings within the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies as well. The National Committee had been appeared alarmed at Martin's complaints about vote splitting, and who was the real Liberal, in November. They met him, but had obtained no satisfaction over his position on the Conciliation Bill. It seems that, anyway, they had no power to rescind the London Committee's invitation to Jacobs to stand, even had they wanted to reverse their own endorsement of it (London Committee Report op cit).

In our modern times of fine-tuned messaging and slick campaign organisation it might seem - looking back - that the whole effort was misconceived. It was surely too big a task for an "independent" to get momentum from a standing-start in a two-week period (which is all they had) with a message that might have been lost to most men on the East St. Pancras omnibus not attuned to the delicate Parliamentary strategising of the Conciliation Committee.

The London Committee however was grateful to Jacobs for putting his head above the parapet, and had evidently sent an "illuminated letter" to him as a token of their appreciation. Jacobs replied graciously "I shall have it framed, and will hang it in some conspicuous place" (letter of May 14 1911, LSE Women's Library). I wonder whether it might still exist somewhere.

Hope, Born Afresh

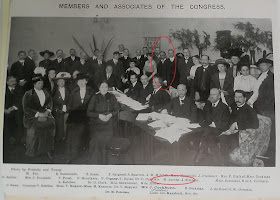

Jacobs remained actively involved in Men's League activities up until its dissolution around World War 1, but we won't go into any more detail now, except to note, following Professor John's investigations, that he was also vice-president of the Jewish League for Women's Suffrage and a director of the International Women's Franchise Club. There had been a strong internationalist flavour to the domestic women's franchise campaign as if to shame HM's Government with examples of Continental, and even Colonial, progress. As we noted last time, P.M. Asquith was deaf to all this. Jacobs is caught in this photo-call at the First Congress of the Men's International Alliance for Women's Suffrage 23-29 October 1912.

|

| With thanks to and © Museum of London |

Herbert's involvement with Jewish organisations and the extent of his self-identification as Jewish, is of interest - but would take us too far afield. Let's note however Tim Harding's mention of him playing a correspondence match with the Manchester Jewish Working Men's Chess Society in 1900-01, and also the reference to Jacobs in the Jewish Museum mentioned at the beginning of this series.

We are not quite finished. There is one - or even two - episodes to go.

Acknowledgements:

With special thanks to Professor Angela John for her interest and encouragement.

Angela V. John, Between the Cause and the Courts: The Curious Case of Cecil Chapman, in Eustace, Ryan and Ugolini (eds), A Suffrage Reader. Charting directions in British suffrage history, Leicester University Press, 2000.

Angela V. John and Claire Eustance (eds), The Men's Share? - Masculinities, Male Support and Women's Suffrage in Britain, 1890-1920, Routledge,1997.

Tim Harding, Correspondence Chess in Britain and Ireland 1824-1987, McFarland, 2010.

Previous episodes: 1. Beginning in Croydon; 2. Brixton, Benedict and Bar; 3.City Champ; 4. Congress Man; 5. A Load of Old Cablers; 6.Engaging Agnes; 7. Congress Man Replayed; 8. Madame Larkcom; 9. Jacobs Crackers; 10. Votes for Women!

And following: 12. Intermission Riff .....14 Still at the Bar 15. Down the Line

Lost in History; and more Chess History

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please do not post anonymously if you have anything controversial to say. Abusive, offensive and legally iffy comments will likely be deleted.