So, our roll-call of Bedlam/Broadmoor chessers included Richard Dadd himself (celebrated artist and parricide), Edward Oxford (regicide-fantasist), Reginald Saunderson (murderer) and also Robert Coombes, the "Wicked Boy" who murdered his mother but redeemed himself, after release, in the trenches of WW1 (the subject of Kate Summerscale's recent book). We also tracked the story of organised chess among patients in Broadmoor: not only their in-house tournaments and the chess column in the house magazine, but also matches against local clubs - about which we had first-hand accounts from a couple of chessers (still at large) who went over to Crowthorne (40 or so miles west of London) in the 1960/70s to play chess at the hospital - and enjoy the excellent refreshments.

More recently we clocked a reappearance of The Child's Problem in an exhibition dedicated to Richard Dadd, and we were delighted to publish this imagined restoration (by blog reader David Roberts) of the work to its former glory, possibly.

All in all a rich vein to dig. So, when this exhibition...

|

| Running until 15 January 2017 |

...opened at the Wellcome Institute in London, naturally your blogger hot-footed over, hoping for another opportunity to savour The Problem. Sadly it wasn't on display (although there was another of Dadd's works): nevertheless, this thought-provoking show offered many other fascinating exhibits, including two with a chess flavour - one familiar, the other less so.

"Thought-provoking" for several reasons. Firstly for its fascinating documentation of the history of "Bedlam" itself, in which it was good to see this again:

|

| From The Illustrated London News on March 1860 (24 March says the exhibition, 31 March says our earlier post), on the occasion of a royal inspection of Bedlam. The artist/engraver is revealed as Frank Vizetelly. |

This unfolding history doesn't duck the issue of whether the "Asylum" - a place of safety and care, mostly; of incarceration and forgetting, often - itself is problematic, maybe outmoded, and should be (indeed already has been) re-thought or re-configured. The narrative is not only historical, it also goes cross-country: I was shocked (by the facts, and one's parochial ignorance) to read in one caption:

|

| The Gallery's Guide and Captions are both on the exhibition website. |

No asylums in Italy! Salutary, too, is the grainy, jerky, footage from 1925 of the annual Procession of St. Dymphna in Geel in Flanders where the "mentally distracted" have been cared for in the community for centuries - out of simple charity, rather than public policy: the villagers take them into their homes. The modern incarnation of Bedlam/Bethlem, without bars, is in Beckenham in South East London, and is remote from the monolithic Victorian Asylum, enlightened though that was in its time.

Another thread weaving through the exhibition is age-old question of who is really sane, if anyone at all. Listen to one Thomas Tryon way back in 1689: "The world is but a great Bedlam where those that are more mad, lock up those who are less"; and another voice from the 1600s, Thomas Middleton (fond of basing his Jacobean dramas on a game at chesse), who wrote "Surely we're all mad people, and they, Whom we think are, are not." And another: that of James Tilley Matthews, a patient said to be incurably insane, who submitted, for a public competition in 1811, an architecturally compos mentis design for a new Bethlem hospital - together with management notes proposing that "the madhouse should become a community in which everyone has a stake." The lunatics will take over this asylum. After all, they designed it. Having said all that - and it makes good copy - there would be concern if such talk should ignore those so disturbed that they maybe a danger to themselves and others; but of course secure facilities, such as at Broadmoor Hospital, are there for that purpose, even in Italy.

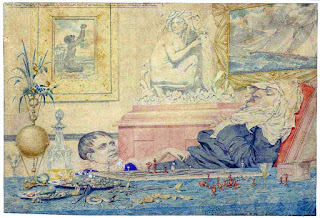

If it wasn't for our Asylum theme, this could almost be a "Chess in Art" post: art is such a strong suit in the exhibition. It shows how conventional art and photography portrayed conditions inside: at its worst to ridicule, sometimes to expose, but also to report sympathetically (even cosmetically - witness the Illustrated London News above). Patients themselves were captured in paint, and photograph - at one time in a grotesque parody of the carte de visite - as if by recording and classifying their outward appearance you could unlock the inward cause of their malady.

And the exhibition shows how art was universally embedded in the life of the therapeutic community: whether giving form to mute protest, inner demons, healing forces, or simply to essential and irrepressible creativity. Richard Dadd was already a Royal Academician before his confinement, but others found, and still do, their talent within the walls. It's on show and on film in the exhibition, including a portrait by Vincent Van Gogh of the care-worn Dr Paul Gachet (1890) who treated the troubled artist after his time in the Saint-Rémy Asylum. Remarkably, it is Van Gogh's "only etching", according to the caption.

|

| From here |

However, the first exhibit you encounter is proper insider art, though firmly on the side of the patients: Eva Kotátková's Asylum (2014). It's so engrossing that you have to remind yourself there are other things to see. It articulates the inner experience of "fears, anxieties, phobias and phantasmagoric visions", and it does so with respect and without grandiloquence (unlike Dali - there is a bit of him later in the exhibition, try as you may to avoid him and his 'paranoiac' attention-seeking). Kotátková objectifies the subjective in this display of her own small scale constructions, along with personal testaments from patients, laid out pêle-mêle for inspection. Phenomenology concrète (if there could be such a thing) would be my label.

The porous border between "Insider" and "Outsider" art - and mentality - is dissolved further in a darkly (and sometimes lightly) humorous film Caligari and the Sleepwalker (2004) made jointly by Javier Téllez and collaborators, together with a group of patients at Vivantes Klinik in Berlin. It is based on the film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari of 1919, and the patients play the characters - holding up a mirror in one scene to the schlafwandler as if to ask us to reflect on the self-delusional derangement of the world outside.

|

| From here |

And we have to thank Javier Téllez again for the other piece of chess in the exhibition: the Schering Chess set of 2015. It ties in another thread: methods of treatment, and the dialogue, synthesis, or dispute - per the orthodoxy of the time - between physical treatments (now drugs, once ECT and lobotomy) and "social" treatments (let's call them) based on interpersonal therapies, aided and abetted by psychological, and behavioral interventions, stretching off to radical "anti-psychiatry" associated mostly prominently with R.D. Laing.

Telléz's chess set quietly critiques the role of big-pharma in the Asylum, the Schering company having been a top player before the brand was itself taken-over. Here is his chess set:

|

Schering Chess (2015) Javier Téllez

Installation, mixed media. 93 x 119 x 119 cm (36 5/8 x 46 7/8 x 46 7/8 in.)

Photos courtesy of the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich

|

It's worth exploring a little. From the shot below you can see the pieces, from rook on the left through to black king, which are repeated on the king's side and on the opposite side of the board with white.

|

| Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich |

From the exhibition caption, and the Galerie Peter Kilchmann, we get an explanation that the board evokes a hospital floor and that the pawn/eggs are associated by the artist with "the mind and its fragility". The pieces are "replicas of pre-Colombian [i.e. the continent of America before the arrival of Colombus in the C15th - MS] ceramics that were used by Schering laboratories to promote psychotropic drugs in the 1970s".

The explanation continues: "The base of each figure features a mental disorder label from the time such as anxiety, depression, or dual emotional distress, highlighting the social and historical dimensions of mental disorder." The base may also name a drug, and in some cases the specific pre-Colombian culture and period providing the source of the figure. Here are close-ups of the labels on the black Queen's Rook and Queen's Knight.

To complete the picture here is an image on-line of the original Schering pieces (not necessarily to be seen as a chess set) as used in their promotions in the 1970s. This group came up for auction in 2015.

|

| "Schering Pharmaceutical PreColumbian [sic] Statue Repros" |

So what are we to make of all this? Firstly, there is the rather ambiguous promotional ploy from Schering laboratories, who enlisted the aid of artifacts from those ancient and only half-understood cultures. Was it intended to be a positive reference: pre-Colombian civilisations using psychoactive agents from plants; one of the Shering figures identified as a "medicine man" from North Peru. Or was it intended to assert the distance between modern scientific drug research as exploited in the Schering labs, and the shamanic sorcery and cult worship of five and more centuries ago. Perhaps, however, they were first and foremost executive toys - paper-weights maybe - whose function was to impress clients and flatter corporate enterprise, in pursuit of a larger share of the market.

Javier Téllez brings the pieces together, remodelled it would seem where necessary, as a chess set - and subtly asks us to ponder these contradictions and beyond: whether drug treatment is itself anything more than a leap of faith, an exercise in magical thinking, or a false prophet: and at root just a convenient way of subduing the patients - and over-sold by the pharma-industry.

But, let's look for a moment at the use of the chess set motif as a polemical-cum-didactic device. Usually, and most effectively, it is employed to make a point about contending ideas - and so we more often see the two sides not only distinguished by colour, but also by modelling. So, in this case, we might have expected to see, on the other side of the board, representations of Laing, Freud, et al., in alliance with others who have deconstructed the Asylum itself: Foucault, Goffman, Basaglia. Such an army would energetically contest the therapeutic efficacy of drugs, dispensed over-zealously, and the hegemonic designs of big-pharma. Though, perhaps this would have been another message, one that Telléz may be sending by means of his other work.

The above - being a marginal observation about the design of one piece in the exhibition from a chess-player's perspective - is not intended to presume to tell (folie de grandeur) mental health professionals how they should go about their business, nor to detract from this particular work or this fascinating exhibition overall. It is not only fascinating, but engaged and opportune also - thus, as I write, some say that wheels may be falling off parts of the Mental Health Service: Professor Dame Sue Bailey of the Children and Young People's Mental Health Coalition says it is a "car crash waiting to happen."

Acknowledgements

The exhibition is accompanied by the excellent This Way Madness Lies by Mike Jay (pub Thames and Hudson (2016)); and see his article 'I'm not signing' in the London Review of Books, 8 September 2016, which reviews The Man Who Closed the Asylums: Franco Basaglia and the Revolution in Mental Health Care by John Foot (pub Verso (2015)).

There's more outsider/insider art currently on show in London here. And there is a permanent exhibition at

Bethlem Museum of the Mind.

Asylum elsewhere

Lost in Art

No comments:

Post a Comment