This series on Herbert Levi Jacobs (1863-1950) ("one of the strongest chess players" in the country, at his peak) continues. We looked at Jacobs' chess in some detail in episodes 1 to 5, and 7, and we will return to it later, but in this one we stick with non-chess themes and continue to examine the significant other in Herbert's life. She emerged fully in episode 6: Charlotte Agnes Larkcom (1856-1931). We'll get back to Herbert and his brief political career in an upcoming episode.

At the end of episode 6 we left him, and his bride-to-be Agnes, just as they were displaying the tell-tale signs of suffragist sympathies. She was about to leave behind her brief celebrity in the field of chess problems (October 1886 is the last reference that I could find), in favour of a more sustained renown in another, and Herbert was about to get stuck into his career in the law. He was called to the bar in 1887, and was thus now secure in his chosen profession. It is maybe consequential that he and Agnes were married the following year: on 14 April 1888. Here they are again, in those photographs as close to the happy event as I have been able to find in publicly available sources (even though it inverts their relative ages).

This is where this episode will start, but it will go well beyond, into the new century, in pursuit of Charlotte Agnes and her independent path.

Earthly Felicity

The marriage was hailed in the British Chess Magazine (June 88) in the course of reporting on City of London Chess Club matters (Herbert was a member, as you will recall from episode 3). The magazine "wish[ed] the happy couple every earthly felicity", though it expressed concern lest the marriage result in "a change of feeling" whereby London Chess might lose "one of its most brilliant younger members." In his anxiety the BCM's correspondent managed not to mention the bride's name, nor her musical gifts - omissions skillfully avoided by the chess columnist of the Thetford and Watton Times (9 June 1888): she was, he said, a "vocalist of ability". The Illustrated London News Chess Chat column of 5 May also managed to give her name, and that she was "a sweet songstress and clever problem solver"; the couple was "a good 'match,' boding well for the future generation of chess players." On balance, then, the chess world had reasons to be cheerful.

(Mrs Herbert Jacobs)

Elsewhere, Florence Fenwick Miller, a staunch suffrage campaigner, who was just embarking on a 32 year-long stint as the Illustrated London News Ladies Columnist, also commented (ILN 7 April). Her column was an idiosyncratic amalgam of fashion notes, waspish observation, and suffrage campaigning. She approved of the couple marrying "quite privately" - an arrangement "in better taste than great crowds of indifferent spectators staring at the most solemn and most private ceremony of life."

Later (May 12) Mrs Fenwick Miller reported on the "party given by Madame Agnes Larkcom (Mrs Herbert Jacobs)...a sort of house-warming to celebrate her return from her wedding trip". Mrs FM critiqued the gowns etc of the female guests: "heliotrope self-coloured broche, with a long train" caught her eye as an especially exotic specimen; and she remarked also on "the earnestness...and self-reliance" of all women-workers - particularly among the many "songstresses" gathered at Agnes's do. She bracketed "(Mrs Herbert Jacobs)" - a sign of things to come, and a nod to Mrs Fenwick Miller's own convictions concerning the naming of wives. She had fought in the courts for the right to use her maiden name even if married (though she herself was later separated), and call herself "Mrs Florence Fenwick Miller". She won, thereby setting a precedent for others to follow.

On the Road Again

The Larkcom-Jacobs marriage was naturally of interest in Agnes's home-town where the Reading Mercury (31 March) recycled a story from the Daily News (n.d) that she "will not quit the profession" - a point repeated by the Glasgow News (16 April), and which encourages us to move the story along. So, almost as soon as they returned from "their wedding trip", she was performing again - for example, in May in Brixton, at a charity concert in London, and on through 1888. And 1889: January - London, Aberdeen, Greenock, Glasgow, Scheveningen (she was to tour Holland twice in her career); February - Leeds; March - Alloa, London (at a charity dinner - she sung during dessert); April - Aberdeen (again - she was popular in Scotland), Kendall...

And so she went on; but let's pause in March 1889 with Mrs Florence Fenwick-Miller again. She dedicated the whole of her Ladies Column of 30 March to the events of the 21st inst., which had begun in the morning with a meeting of the National Society for Women's Suffrage (NSWS), and culminated with an evening indoor rally on Women's Suffrage in the Princes Hall: "The great audience which crowded the hall remained almost unbroken in numbers till after eleven at night."

Parliamentary procedure

Her column gave an update on the pro-suffrage campaign: the issue at hand was a clause in a Bill before the Commons which proposed extending the parliamentary franchise to single women and widows (a useful stepping stone, argued some), yet "specifically excludes duly-qualified married women". Mrs Fenwick Miller said that she had herself proposed opposition to this compromised measure at the members' meeting of the NSWS, and her article invoked two pioneers of total Women's Suffrage in support: John Stuart Mill (who lost his seat in 1870), and Joseph Bright MP. Both Mills and Bright are mentioned later by Jacobs as influences on his thinking (as we shall see in a later episode). I should add, perhaps - by way of a disclaimer - that the tortuous complexities of late 19th and early 20th Century suffrage qualifications, male, female, actual and proposed, are sometimes beyond me (it's so much easier just to give the vote to everyone) - apologies if I have inadvertently misrepresented the state of play in 1889.

At the evening rally Mrs FM had spotted Agnes, and once again she leavened her account with fashion notes à la mode. The "very pretty" Madame Larkcom was "in a becoming green Empire bonnet, with a pink rose-wreath filling up the rim and another surrounding the crown". An illustration may help.

Also on display, incidentally, was Miss Florence Balgarnie, the Secretary of the NSWS, with her (pun alert) "very 'bonny' aspect". You'll remember Miss Balgarnie from episode 3. She was a guest at the Inns of Court chess match in July 88, in which Jacobs and left-leaning Liberal MP Llewellyn Atherley-Jones were both playing.

So Agnes was in the thick of it, and it's a safe bet the Herbert was there, too. Professionally, her concert performances continued unabated, and the press of the day gave many notices and reviews of her soprano performances (solo, chamber, full choral works), in London, the provinces, and further afield in the years 1890 to 1893 - seemingly every month without exception. She may also be found in fashionable London society on the guest list of the Lord Mayor's bash at the Mansion House (the Era 11 Nov 1893) - as "Madame Agnes Larkcom", with "Mr Herbert Jacobs" alongside.

Career Move

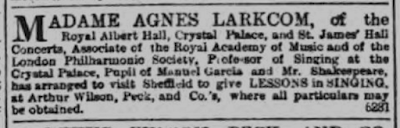

By now (the 90s), Madame Larkcom (well into her 30s), was effecting a transition from performer to professor. Indeed, the 1891 census showed her (aged 35) as a "Professor of Music" (at that stage just a voice coach to a choral ensemble) living at 53, Westbourne Park Villas, Paddington with Herbert (27) - also Agnes's elderly mother and one servant. Agnes appears to be near the summit of her career, with the best part of two decades of experience to inform her teaching. In 1893 she appeared in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph 11 February offering "lessons in singing"...

...and in 1894 she was appointed to the prestigious post of Professor of Music at the Royal Academy of Music, though "Lute" in "Notes from the Concert Room" in The Sketch of 24 February 1894 managed royally to mangle the announcement: "I am glad to chronicle the election of Mrs Jacob (sic doubled) to a vocal professorship at the Royal Academy of Music. The lady will be pleasantly remembered in many a concert room under her maiden name of Agnes Larkcom, and is most efficient to train others to reap the success she so long enjoyed." 1894 was the year that Herbert finally won the championship of the City of London Chess Club, after nearly a decade of trying.

New Arrival

Around this time Agnes and Jacob were successful, after seven years of marriage, in a singularly joint enterprise: on 21 January 1895 Eric Herbert Jacobs-Larkcom was born. The birth was registered in Truro for reasons as yet unclear to me. The last concert that Agnes gave before his birth appears to have been in November 1894. Agnes then stopped performing for 3 months, until a concert in March 1895. A working-class woman would likely have had to contend with greater rigours than middle-class Agnes, but to bear a child at the age of 38, enduring Victorian midwifery and perinatal care, and be back on the concert platform so soon, is impressive.

However, that concert in March 1895 seemed to have been a one-off, and maybe she decided that touring was too demanding, because there was a sea-change in Agnes's working pattern from 1895 onward. The evidence comes, once again, from references to her in the British Newspaper Archive (BNA). She had to withdraw from a singing engagement in March 1896 due to an indisposition; thereafter there were only very occasional concerts advertised or reported (for example, only one in 1899 in London, and that was performed by her pupils). Instead she was giving singing lessons: regularly in Sheffield, occasionally in Cardiff and Hull.

Among the other commitments she would have had as a Professor at the Royal Academy of Music, she could be found examining for, and awarding, scholarships, including the Westmorland (Evening Standard 20 Dec 1897), which she had won herself over 20 years previously. Herbert, incidentally, was as active as ever on the chess scene, not only at club level, but also increasingly in Congresses - and the cable matches - as we have documented in earlier episodes (his legal career will be factored in later in the series).

Double Portrait

In the 1901 census (taken 31 March) the household is at 57 Talbot Road, Highgate, now with two servants. and Herbert shown as a barrister, though no profession is entered for Agnes, However, the BNA throws up some interesting references to the Jacobs/Larkcoms in that decade, putting them in Bucklebury near Reading, suggesting some kind of re-connection by Agnes with her childhood roots. In fact she performed at the Parish concert on the 10th April 1901 "in spite of a cold" (Reading Mercury 27 April), and was described as a "gifted parishioner" suggesting that she was already well established locally.

They were living at "Gorselands" in Bucklebury in 1906 (Berkshire Chronicle 10 March), when she made another local performance - in aid of the Reading Soup Kitchen. Her contribution to community life was apparent earlier when she was called on to judge the needlework class in the Bucklebury and Marlston Horticultural Show in the summer of 1903 (Reading Mercury 22 August), a pleasant duty she shared with Mrs Bate. Among those "principal residents" noted at the Show was Mrs Bate's husband Francis "a prominent figure in Berkshire" (McConkey (2006)) - and a prominent figure also, in the 1890s, in the New English Art Club, an alternative to the artistic establishment of the day, before itself settling down "in a sane and sober maturity" (St.James's Gazette 15 April 1902).

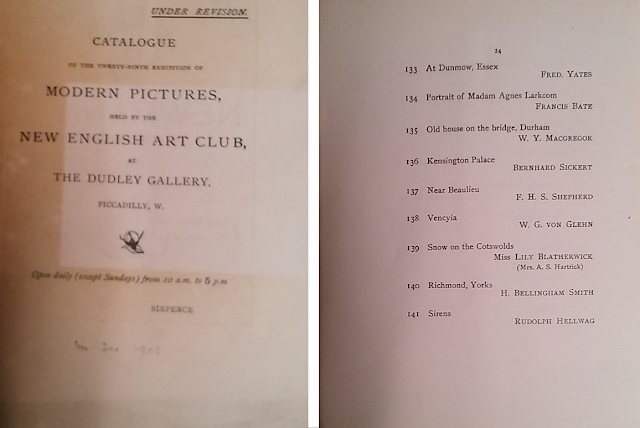

Bate painted portraits of both Herbert and Agnes. Herbert's portrait was exhibited at the NEAC in 1902 and described as "notable" in the St. James's Gazette. The Globe (5 April) goes further: "it is commendable for its vitality and honest presentation of a definite personality." Agnes's was exhibited later in the NEAC winter show where it was also enthusiastically received. It showed all Bate's "usual strength of characterisation and directness of statement, and besides, a greater charm of colour than he has attained for some time past." (The Globe 8 November 1902). My search for reproductions of the portraits in the usual on-line resources has drawn a blank. Here is the best I can do for Agnes - her exhibition catalogue entry.

If the portraits are still extant they may be in private ownership: it would be nice to find them. Here, instead, is one Mr Bate did earlier:

Keeping Active

We are now on the threshold of Herbert's political moment. It had been cooking for some time, as he later indicated, but the breakout year was 1907 when he founded the Men's League for Women's Suffrage, which he then chaired. Son Eric was by now 12 years old. In 1910 Herbert stood for parliament, albeit unsuccessfully. As already signalled, we will relate this fascinating adventure in a forthcoming episode.

Agnes's contribution to the cause was more muted. She was a founder member of the Society of Women Musicians in 1911 formed to provide a supportive space for female musicians and composers to network (as we would call it). Agnes was President in 1923-4.

The SWM was not a suffragist organisation though some of its leading members did not hide their sympathies - though (oddly, perhaps) Ethel Smyth, famously the composer of "The March of the Women" (the suffragist anthem), had only "an erratic relationship" with the organisation (a quote from Seddon (2011)). By the way, Agnes (and Eric) seem not to be in the 1911 census (there was a suffragist boycott), though Herbert is there at 57, Talbot Road.

In 1918 Agnes committed her accumulated wisdom and knowledge to a paper which she read to the SWM: The Art of Teaching Singing. It was reprinted in the Musical Times 1 June 1918 which described her as "one of the best-known and highly esteemed teachers of singing in London". She took the opportunity to make the following declaration:

Travel, writing

After the war Agnes travelled extensively. She was celebrated in Australia, which she visited in 1921, where she told a local paper (Adelaide Advertiser 6 July) that she had "left England nearly 12 months ago" and had visited the States, Japan and China (to see Eric out there on duty). She went on to list the various prima donnas she had trained over the years, commenting that at the RAM she was not allowed to teach men...

Other observations on music and the art of singing (from lectures given at the Royal College of Music in 1924 and 1926) were included in a collection of essays she published in 1928 (when she was 72). The collection was titled "Loneliness and other essays", and would seem that theme of the principal essay was a reflection on aspects of her personal life, specifically the absence of her son Eric on military duties. But firstly, note that back in 1912 Agnes had changed her surname by deed poll to "Agnes Jacobs-Larkhom" (Falkirk Herald 9 Sep 1912, also announced in the Times) - the same surname as had been registered for Eric at his birth. Without going off too far at another tangent: Eric Jacobs-Larkcom had entered the Army on a commission in 1916, and then after the WW1 served in China, continuing there through WW2 (albeit with a stint in Europe including evacuation from Dunkirk), then transferring to the Foreign Service in the Far East until his retirement in 1958. He started a family in 1935, and his children (Agnes and Herbert's grandchildren) are still with us.

In the light of Eric's military service one can appreciate Agnes's Anguish (the title of another of her essays) as her son went off to the front in WW1; and her essay Loneliness - the book is dedicated to "my dear son Eric" - speaks of the mother who "fears and realises that she is no longer the one necessity of [her children's] lives...The sense of loneliness encompasses her and grows more and more insistent". One can, of course, sympathise: but I must confess that otherwise her writing does not appeal to me, nor, I suspect, will it to the modern reader generally. So here, for balance, is a contemporaneous assessment from Oz (Adelaide Advertiser 7 July 1928): "In a pleasant and unpretentious style, and with a mind fortified by wide reading, she discourses....in a way calculated to stimulate thought." However, you can almost hear the reviewer raise an eye-brow as "Miss (sic) Larkcom is not complementary to her sex", going on to add (including a quote from her essay) "what male critic would be so ungallant as to declare that 'the female form is rarely quite beautiful?'" - the latter being Agnes's thumbs down a propos the revelations occasioned by the short tennis skirts then in fashion on court.

Conclusion

Agnes died in 1931, aged 75, with an obit in the Musical Times of August 1 that year: "she had considerable influence upon the standard of singing in this country." Overall, she had clearly been a determined and independent woman who stood in the proto-feminist corner by pursuing her own professional career separate from her husband. Yet, in the fight for female suffrage, where their outlooks converged, it is difficult to form any picture of the Jacobs-Larkcom marriage as one of conjoint conjugal activism in the way of other couples (the Fawcetts, the Pethick-Lawrences). Herbert and Agnes appeared to plough parallel furrows, even when their politics overlapped. If her rather sentimental writing in Loneliness strikes today's reader as antique Victoriana, in other respects she was more 20th Century than 19th. In spite of the intimations of loneliness in her book, and her extended trips abroad, it seems that she and Herbert remained a couple, together still in old age. She left her estate of nearly £7,000 (almost £500k today) to Eric.

Next time: back to Herbert.

For all episodes on Herbert Jacobs before and after this one go to Lost in History

References

Larkcom, Agnes J. (1928) Loneliness and other essays. Duckworth, London.

McConkey, Kenneth (2006) The New English Art Club. Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Seddon, Laura (2011) The instrumental music of British Women Composers in the Early Twentieth Century. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, City University London. On line here.

At the end of episode 6 we left him, and his bride-to-be Agnes, just as they were displaying the tell-tale signs of suffragist sympathies. She was about to leave behind her brief celebrity in the field of chess problems (October 1886 is the last reference that I could find), in favour of a more sustained renown in another, and Herbert was about to get stuck into his career in the law. He was called to the bar in 1887, and was thus now secure in his chosen profession. It is maybe consequential that he and Agnes were married the following year: on 14 April 1888. Here they are again, in those photographs as close to the happy event as I have been able to find in publicly available sources (even though it inverts their relative ages).

|

| Agnes aged 21 in 1877, and Herbert aged 32 in 1895 |

Earthly Felicity

The marriage was hailed in the British Chess Magazine (June 88) in the course of reporting on City of London Chess Club matters (Herbert was a member, as you will recall from episode 3). The magazine "wish[ed] the happy couple every earthly felicity", though it expressed concern lest the marriage result in "a change of feeling" whereby London Chess might lose "one of its most brilliant younger members." In his anxiety the BCM's correspondent managed not to mention the bride's name, nor her musical gifts - omissions skillfully avoided by the chess columnist of the Thetford and Watton Times (9 June 1888): she was, he said, a "vocalist of ability". The Illustrated London News Chess Chat column of 5 May also managed to give her name, and that she was "a sweet songstress and clever problem solver"; the couple was "a good 'match,' boding well for the future generation of chess players." On balance, then, the chess world had reasons to be cheerful.

(Mrs Herbert Jacobs)

Elsewhere, Florence Fenwick Miller, a staunch suffrage campaigner, who was just embarking on a 32 year-long stint as the Illustrated London News Ladies Columnist, also commented (ILN 7 April). Her column was an idiosyncratic amalgam of fashion notes, waspish observation, and suffrage campaigning. She approved of the couple marrying "quite privately" - an arrangement "in better taste than great crowds of indifferent spectators staring at the most solemn and most private ceremony of life."

|

| Mrs Fenwick Miller (1854-1936) in full sail. Pic from NPG |

Later (May 12) Mrs Fenwick Miller reported on the "party given by Madame Agnes Larkcom (Mrs Herbert Jacobs)...a sort of house-warming to celebrate her return from her wedding trip". Mrs FM critiqued the gowns etc of the female guests: "heliotrope self-coloured broche, with a long train" caught her eye as an especially exotic specimen; and she remarked also on "the earnestness...and self-reliance" of all women-workers - particularly among the many "songstresses" gathered at Agnes's do. She bracketed "(Mrs Herbert Jacobs)" - a sign of things to come, and a nod to Mrs Fenwick Miller's own convictions concerning the naming of wives. She had fought in the courts for the right to use her maiden name even if married (though she herself was later separated), and call herself "Mrs Florence Fenwick Miller". She won, thereby setting a precedent for others to follow.

On the Road Again

The Larkcom-Jacobs marriage was naturally of interest in Agnes's home-town where the Reading Mercury (31 March) recycled a story from the Daily News (n.d) that she "will not quit the profession" - a point repeated by the Glasgow News (16 April), and which encourages us to move the story along. So, almost as soon as they returned from "their wedding trip", she was performing again - for example, in May in Brixton, at a charity concert in London, and on through 1888. And 1889: January - London, Aberdeen, Greenock, Glasgow, Scheveningen (she was to tour Holland twice in her career); February - Leeds; March - Alloa, London (at a charity dinner - she sung during dessert); April - Aberdeen (again - she was popular in Scotland), Kendall...

And so she went on; but let's pause in March 1889 with Mrs Florence Fenwick-Miller again. She dedicated the whole of her Ladies Column of 30 March to the events of the 21st inst., which had begun in the morning with a meeting of the National Society for Women's Suffrage (NSWS), and culminated with an evening indoor rally on Women's Suffrage in the Princes Hall: "The great audience which crowded the hall remained almost unbroken in numbers till after eleven at night."

Parliamentary procedure

Her column gave an update on the pro-suffrage campaign: the issue at hand was a clause in a Bill before the Commons which proposed extending the parliamentary franchise to single women and widows (a useful stepping stone, argued some), yet "specifically excludes duly-qualified married women". Mrs Fenwick Miller said that she had herself proposed opposition to this compromised measure at the members' meeting of the NSWS, and her article invoked two pioneers of total Women's Suffrage in support: John Stuart Mill (who lost his seat in 1870), and Joseph Bright MP. Both Mills and Bright are mentioned later by Jacobs as influences on his thinking (as we shall see in a later episode). I should add, perhaps - by way of a disclaimer - that the tortuous complexities of late 19th and early 20th Century suffrage qualifications, male, female, actual and proposed, are sometimes beyond me (it's so much easier just to give the vote to everyone) - apologies if I have inadvertently misrepresented the state of play in 1889.

|

| Jacob Bright (1811-1889 ) and John Stuart Mill (1806-1873 ) From Tatler May 5 1877 and Vanity Fair May 29 1973 |

At the evening rally Mrs FM had spotted Agnes, and once again she leavened her account with fashion notes à la mode. The "very pretty" Madame Larkcom was "in a becoming green Empire bonnet, with a pink rose-wreath filling up the rim and another surrounding the crown". An illustration may help.

|

| Not green, nor garlanded with roses (and nor is it Agnes), but "gathered black satin", and (in spite of some opposition to the practice) embellished with black ostrich feathers. |

Also on display, incidentally, was Miss Florence Balgarnie, the Secretary of the NSWS, with her (pun alert) "very 'bonny' aspect". You'll remember Miss Balgarnie from episode 3. She was a guest at the Inns of Court chess match in July 88, in which Jacobs and left-leaning Liberal MP Llewellyn Atherley-Jones were both playing.

So Agnes was in the thick of it, and it's a safe bet the Herbert was there, too. Professionally, her concert performances continued unabated, and the press of the day gave many notices and reviews of her soprano performances (solo, chamber, full choral works), in London, the provinces, and further afield in the years 1890 to 1893 - seemingly every month without exception. She may also be found in fashionable London society on the guest list of the Lord Mayor's bash at the Mansion House (the Era 11 Nov 1893) - as "Madame Agnes Larkcom", with "Mr Herbert Jacobs" alongside.

Career Move

By now (the 90s), Madame Larkcom (well into her 30s), was effecting a transition from performer to professor. Indeed, the 1891 census showed her (aged 35) as a "Professor of Music" (at that stage just a voice coach to a choral ensemble) living at 53, Westbourne Park Villas, Paddington with Herbert (27) - also Agnes's elderly mother and one servant. Agnes appears to be near the summit of her career, with the best part of two decades of experience to inform her teaching. In 1893 she appeared in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph 11 February offering "lessons in singing"...

...and in 1894 she was appointed to the prestigious post of Professor of Music at the Royal Academy of Music, though "Lute" in "Notes from the Concert Room" in The Sketch of 24 February 1894 managed royally to mangle the announcement: "I am glad to chronicle the election of Mrs Jacob (sic doubled) to a vocal professorship at the Royal Academy of Music. The lady will be pleasantly remembered in many a concert room under her maiden name of Agnes Larkcom, and is most efficient to train others to reap the success she so long enjoyed." 1894 was the year that Herbert finally won the championship of the City of London Chess Club, after nearly a decade of trying.

New Arrival

Around this time Agnes and Jacob were successful, after seven years of marriage, in a singularly joint enterprise: on 21 January 1895 Eric Herbert Jacobs-Larkcom was born. The birth was registered in Truro for reasons as yet unclear to me. The last concert that Agnes gave before his birth appears to have been in November 1894. Agnes then stopped performing for 3 months, until a concert in March 1895. A working-class woman would likely have had to contend with greater rigours than middle-class Agnes, but to bear a child at the age of 38, enduring Victorian midwifery and perinatal care, and be back on the concert platform so soon, is impressive.

However, that concert in March 1895 seemed to have been a one-off, and maybe she decided that touring was too demanding, because there was a sea-change in Agnes's working pattern from 1895 onward. The evidence comes, once again, from references to her in the British Newspaper Archive (BNA). She had to withdraw from a singing engagement in March 1896 due to an indisposition; thereafter there were only very occasional concerts advertised or reported (for example, only one in 1899 in London, and that was performed by her pupils). Instead she was giving singing lessons: regularly in Sheffield, occasionally in Cardiff and Hull.

Among the other commitments she would have had as a Professor at the Royal Academy of Music, she could be found examining for, and awarding, scholarships, including the Westmorland (Evening Standard 20 Dec 1897), which she had won herself over 20 years previously. Herbert, incidentally, was as active as ever on the chess scene, not only at club level, but also increasingly in Congresses - and the cable matches - as we have documented in earlier episodes (his legal career will be factored in later in the series).

Double Portrait

In the 1901 census (taken 31 March) the household is at 57 Talbot Road, Highgate, now with two servants. and Herbert shown as a barrister, though no profession is entered for Agnes, However, the BNA throws up some interesting references to the Jacobs/Larkcoms in that decade, putting them in Bucklebury near Reading, suggesting some kind of re-connection by Agnes with her childhood roots. In fact she performed at the Parish concert on the 10th April 1901 "in spite of a cold" (Reading Mercury 27 April), and was described as a "gifted parishioner" suggesting that she was already well established locally.

They were living at "Gorselands" in Bucklebury in 1906 (Berkshire Chronicle 10 March), when she made another local performance - in aid of the Reading Soup Kitchen. Her contribution to community life was apparent earlier when she was called on to judge the needlework class in the Bucklebury and Marlston Horticultural Show in the summer of 1903 (Reading Mercury 22 August), a pleasant duty she shared with Mrs Bate. Among those "principal residents" noted at the Show was Mrs Bate's husband Francis "a prominent figure in Berkshire" (McConkey (2006)) - and a prominent figure also, in the 1890s, in the New English Art Club, an alternative to the artistic establishment of the day, before itself settling down "in a sane and sober maturity" (St.James's Gazette 15 April 1902).

Bate painted portraits of both Herbert and Agnes. Herbert's portrait was exhibited at the NEAC in 1902 and described as "notable" in the St. James's Gazette. The Globe (5 April) goes further: "it is commendable for its vitality and honest presentation of a definite personality." Agnes's was exhibited later in the NEAC winter show where it was also enthusiastically received. It showed all Bate's "usual strength of characterisation and directness of statement, and besides, a greater charm of colour than he has attained for some time past." (The Globe 8 November 1902). My search for reproductions of the portraits in the usual on-line resources has drawn a blank. Here is the best I can do for Agnes - her exhibition catalogue entry.

|

| Agnes in at no. 134. W.G. von Glehn at no. 138 was also a female suffrage supporter. |

|

| Francis Bate (1853-1950) A girl reading by a river (c1892) |

Keeping Active

We are now on the threshold of Herbert's political moment. It had been cooking for some time, as he later indicated, but the breakout year was 1907 when he founded the Men's League for Women's Suffrage, which he then chaired. Son Eric was by now 12 years old. In 1910 Herbert stood for parliament, albeit unsuccessfully. As already signalled, we will relate this fascinating adventure in a forthcoming episode.

Agnes's contribution to the cause was more muted. She was a founder member of the Society of Women Musicians in 1911 formed to provide a supportive space for female musicians and composers to network (as we would call it). Agnes was President in 1923-4.

|

| The SWM inaugural meeting, though sadly Agnes was not snapped among the assembled ladies. From The Sphere 25 November 1911 |

The SWM was not a suffragist organisation though some of its leading members did not hide their sympathies - though (oddly, perhaps) Ethel Smyth, famously the composer of "The March of the Women" (the suffragist anthem), had only "an erratic relationship" with the organisation (a quote from Seddon (2011)). By the way, Agnes (and Eric) seem not to be in the 1911 census (there was a suffragist boycott), though Herbert is there at 57, Talbot Road.

In 1918 Agnes committed her accumulated wisdom and knowledge to a paper which she read to the SWM: The Art of Teaching Singing. It was reprinted in the Musical Times 1 June 1918 which described her as "one of the best-known and highly esteemed teachers of singing in London". She took the opportunity to make the following declaration:

"The Society numbers among its members a good many women who have had wide experience both as performers and teachers, and I feel strongly that the moment has come when we ought not longer to sit down tamely and allow men alone to decide what we can and what we can not do, what is right and what is wrong, and in fact take up the position of final arbiters with regard to our development mentally and artistically. I consider women know best about their own physical powers and limitations, and I also think we ought to establish a standard of taste and excellent of performance for ourselves, and endeavor to help the younger members of the Society by giving them the benefit of the collective experience of those of us who have had wider opportunities. Women are apt to be timid and afraid to assert themselves—if they hold original views, they give them up too readily if a man comes along and attacks them. I am inclined to hope that if various aspects of the art of singing and teaching singing were dispassionately discussed here, we might feel more certain of ourselves and be able to inspire the less experienced members of the Society with greater confidence and enthusiasm."She published her talk, with additional material, as The Singer's Art in 1920.

Travel, writing

After the war Agnes travelled extensively. She was celebrated in Australia, which she visited in 1921, where she told a local paper (Adelaide Advertiser 6 July) that she had "left England nearly 12 months ago" and had visited the States, Japan and China (to see Eric out there on duty). She went on to list the various prima donnas she had trained over the years, commenting that at the RAM she was not allowed to teach men...

Other observations on music and the art of singing (from lectures given at the Royal College of Music in 1924 and 1926) were included in a collection of essays she published in 1928 (when she was 72). The collection was titled "Loneliness and other essays", and would seem that theme of the principal essay was a reflection on aspects of her personal life, specifically the absence of her son Eric on military duties. But firstly, note that back in 1912 Agnes had changed her surname by deed poll to "Agnes Jacobs-Larkhom" (Falkirk Herald 9 Sep 1912, also announced in the Times) - the same surname as had been registered for Eric at his birth. Without going off too far at another tangent: Eric Jacobs-Larkcom had entered the Army on a commission in 1916, and then after the WW1 served in China, continuing there through WW2 (albeit with a stint in Europe including evacuation from Dunkirk), then transferring to the Foreign Service in the Far East until his retirement in 1958. He started a family in 1935, and his children (Agnes and Herbert's grandchildren) are still with us.

In the light of Eric's military service one can appreciate Agnes's Anguish (the title of another of her essays) as her son went off to the front in WW1; and her essay Loneliness - the book is dedicated to "my dear son Eric" - speaks of the mother who "fears and realises that she is no longer the one necessity of [her children's] lives...The sense of loneliness encompasses her and grows more and more insistent". One can, of course, sympathise: but I must confess that otherwise her writing does not appeal to me, nor, I suspect, will it to the modern reader generally. So here, for balance, is a contemporaneous assessment from Oz (Adelaide Advertiser 7 July 1928): "In a pleasant and unpretentious style, and with a mind fortified by wide reading, she discourses....in a way calculated to stimulate thought." However, you can almost hear the reviewer raise an eye-brow as "Miss (sic) Larkcom is not complementary to her sex", going on to add (including a quote from her essay) "what male critic would be so ungallant as to declare that 'the female form is rarely quite beautiful?'" - the latter being Agnes's thumbs down a propos the revelations occasioned by the short tennis skirts then in fashion on court.

Conclusion

Agnes died in 1931, aged 75, with an obit in the Musical Times of August 1 that year: "she had considerable influence upon the standard of singing in this country." Overall, she had clearly been a determined and independent woman who stood in the proto-feminist corner by pursuing her own professional career separate from her husband. Yet, in the fight for female suffrage, where their outlooks converged, it is difficult to form any picture of the Jacobs-Larkcom marriage as one of conjoint conjugal activism in the way of other couples (the Fawcetts, the Pethick-Lawrences). Herbert and Agnes appeared to plough parallel furrows, even when their politics overlapped. If her rather sentimental writing in Loneliness strikes today's reader as antique Victoriana, in other respects she was more 20th Century than 19th. In spite of the intimations of loneliness in her book, and her extended trips abroad, it seems that she and Herbert remained a couple, together still in old age. She left her estate of nearly £7,000 (almost £500k today) to Eric.

Next time: back to Herbert.

For all episodes on Herbert Jacobs before and after this one go to Lost in History

References

Larkcom, Agnes J. (1928) Loneliness and other essays. Duckworth, London.

McConkey, Kenneth (2006) The New English Art Club. Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Seddon, Laura (2011) The instrumental music of British Women Composers in the Early Twentieth Century. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis, City University London. On line here.

No comments:

Post a Comment